Le Musée et son Double

Provoking public architecture. Seven interlocking movements.

The Ghent Museum of Contemporary Art (S.M.A.K.) evidences an intriguing case of ongoing fortuity. Often in an absurd manner. This propensity can doubtlessly be applied to the collection’s build-up1, yet in an even more striking way this fortuitous trait is most noticeable through the museum’s challenging relationship with (its own) architecture and public space. Since its informal inception in 1957, the Ghent Museum of Contemporary Art has been struggling, lobbying, toiling, …, for an adequate home front, a public shelter capable to house both the collection and the museum’s daily operation. At present, the collection and the artistic direction enjoy international acclaim. The contrast with its built (museum) architecture could not be bigger. Over the past decades, the museum has never shied away from actively putting this discrepancy on the political agenda, often through intelligent detours such as public activism and extra muros exhibitions2. However, after more than 60 years of exemplary and adventurous3 museum practice, the time has finally come to renew the museum’s infrastructure and architecture, while firmly anchoring its base in the centre of Ghent.

This text attempts to reconstruct the museum’s spatial evolution through 7 chapters, tied together through moments of artistic criticality, public provocation and architectural (non-) intentionality. The last chapter – The Double Museum – is somewhat particular. If the first 6 chapters clearly refer to past and established actions, the 7th chapter is actually unfolding as we speak (or write this text). It seeks to foreshadow the future architectural position of the S.M.A.K. Entitled ‘The Double Museum’, chapter. 7 is clearly a provocation in itself, true to the museum’s ethos and its on-going cultural practice of problematizing social issues. ‘The Double Museum’ presents a clear architectural typology, an unsuspected yet exciting spatial equilibrium, that will allow the museum to focus on one single essential task: shaping the collection.

ONE (1957)

The friends’ museum … On November 8th 1957, the ‘Society for the Ghent Museum of Contemporary Art’ was founded by a group of local art enthusiasts and collectors. The venture’s main ambition was to establish an autonomous city museum aimed towards the presentation of contemporary art, both locally and internationally. A series of significant art shows combined with a sensible acquisition policy led to the establishment of a foundation for an actual Museum of Contemporary Art in Ghent. During these 18 preparatory years, the Society exerted a profound and persistent influence on the build-up of the collection of the future museum, although up to that point the ‘friends of the museum’ failed to establish an actual physical museum.

TWO (1975)

The cohabiting museum … In 1975, the Ghent Museum of Contemporary Art was established. Since the museum originated at the Ghent Museum of Fine Arts, home to the ‘Society for the Ghent Museum of Contemporary Art’, the Museum of Fine Arts became the logical first spatial base for the new Ghent Museum of Contemporary Art. The Neoclassical symmetrical architecture authored by Charles Van Rysselberghe (1904 & 1913), presented an almost natural space for cohabitation, in which each collection4 was provided with a fully-fledged and agonistic ‘exhibition-playground’. In 1975, the museum’s first ever director was appointed (Jan Hoet). From the onset, he paired his provocative museum and exhibition policy with a call for an autonomous museum building. It would take until 1999 before the latter ambition was (partially) realized. Until then, the museum was condemned to cohabitation.

THREE (1986)

The extra muros museum … One of Hoet’s remarkable realizations was the exhibition Chambres d’Amis, which celebrated the museum’s first decade. Throughout the entire city of Ghent, 51 contemporary art works were publicly displayed at as many private houses. Parallel to the Chambres d’Amis exhibition, the ‘Society for the Museum of Contemporary Art’ ran the equally remarkable Initiatief 86 show. Both extra muros exhibitions could be understood as a clear call for the realignment of the museum’s engagement with its social and urban context. Meanwhile, the urgency for a proper museum building became increasingly acute. In those days, the Ghent Museum of Contemporary Art was commonly known as the ‘ghost museum’5.

FOUR (1996/99)

The old new museum … Finally, in 1993, the city of Ghent decided on the museum’s future accommodation. The former Casino Building, part of the Floralia complex (1913) adjacent to the Ghent Museum of Fine Arts was to become the ‘new’ shell for contemporary art. Located in the Citadel Park, the whole Floralia complex is somewhat of an oddity, having been rebuilt, extended and refurbished endless times. To put it bluntly, the Floralia complex is nothing less than an architectural Frankenstein. At its heart lies the Floralia Hall6, enveloped by the velodrome of ’t Kuipke and a generic International Congress Centre, both venues clearly oversized in comparison with the fragile scale of the Citadel Park. In 1996, a first part of the Museum of Contemporary Art was inaugurated, offering one wing of the Floralia complex that was converted into an art depot. For the opening event, called De Rode Poort, Luc Deleu & T.O.P. office installed a temporary shipyard access, while next door in the Casino Building the works for the future museum simply carried on. Despite Jan Hoet’s insistence on an international architectural competition, the city of Ghent directly assigned its administrative city architect to build the museum. This uncritical move implied that the museum’s architecture would never surpass the level of perfunctory compromise it eventually turned out to be. Officially it was stated that this ‘new’ museum was an overt critique on the prevailing spectacular European museum architecture, championing an building culture that was subservient to the practice of exhibiting art. On May 6th 1999, the museum opened its doors to the public under a new name: the ‘S.M.A.K.’. Despite the meagre architectural achievement, the opening ceremony managed to perfectly point out the underlying potential of the Floralia complex. The map of the inauguration event clearly shows how the whole Frankenstein is suddenly and excitingly brought to life. After the launch party, the museum folded back onto its new footprint, which soon proved to be far too small.

FIVE (2001)

the oxygenic museum … Temporary expansions of the museum were frequently attempted. One of the most convincing efforts was the 2001 Panamarenko show. Clearly a new nexus for the museum’s on-going endeavour to realize the ‘ideal’ museum and achieve broad-scale public interaction. Partially due to the monumental scale of the artist’s work, but equally as a provocative positioning, the Floralia Hall became a natural expansion of the S.M.A.K. A similar effect was achieved with the 2008 Paul McCarthy show. On the basis of these experiments it can be concluded that the S.M.A.K. indeed requires a museum architecture that is adaptable, malleable and able to accommodate large-scale works. In short, oxygen.

SIX (2005)

the undersized museum … At the start of his term as museum director, Philippe van Cauteren consciously launched 2 mantras. The first had to do with the collection, and the fact that at least 500 works should be permanently put on display. The second concerned the inadequate space of the museum, which was articulated as ‘the museum should be twice as big’. ‘500’ and ‘2’ as extremely powerful sublimation strategies. Over the past 15 years, the mantras haven’t changed at all. In the meantime, however, the city’s administration did undertake, in a rather feverish manner, numerous attempts to study manifold expansion scenarios. Strangely enough, all these schemes took only one basic option into consideration: demolish the current S.M.A.K. and build a new museum at the same spot. The problem here is the number ‘2’, as the doubling the volume of the S.M.A.K., even partially underground, would definitely result in an absolutely disproportionate ‘zit’ in the Citadel Park. A cursory observer would probably conclude that it is simply impossible to build a new S.M.A.K. in the park. Yet, if we turn this around, and consider number ‘2’ not as a problem, but understand it as a true chance, a compelling new museum typology comes into being: the double museum.

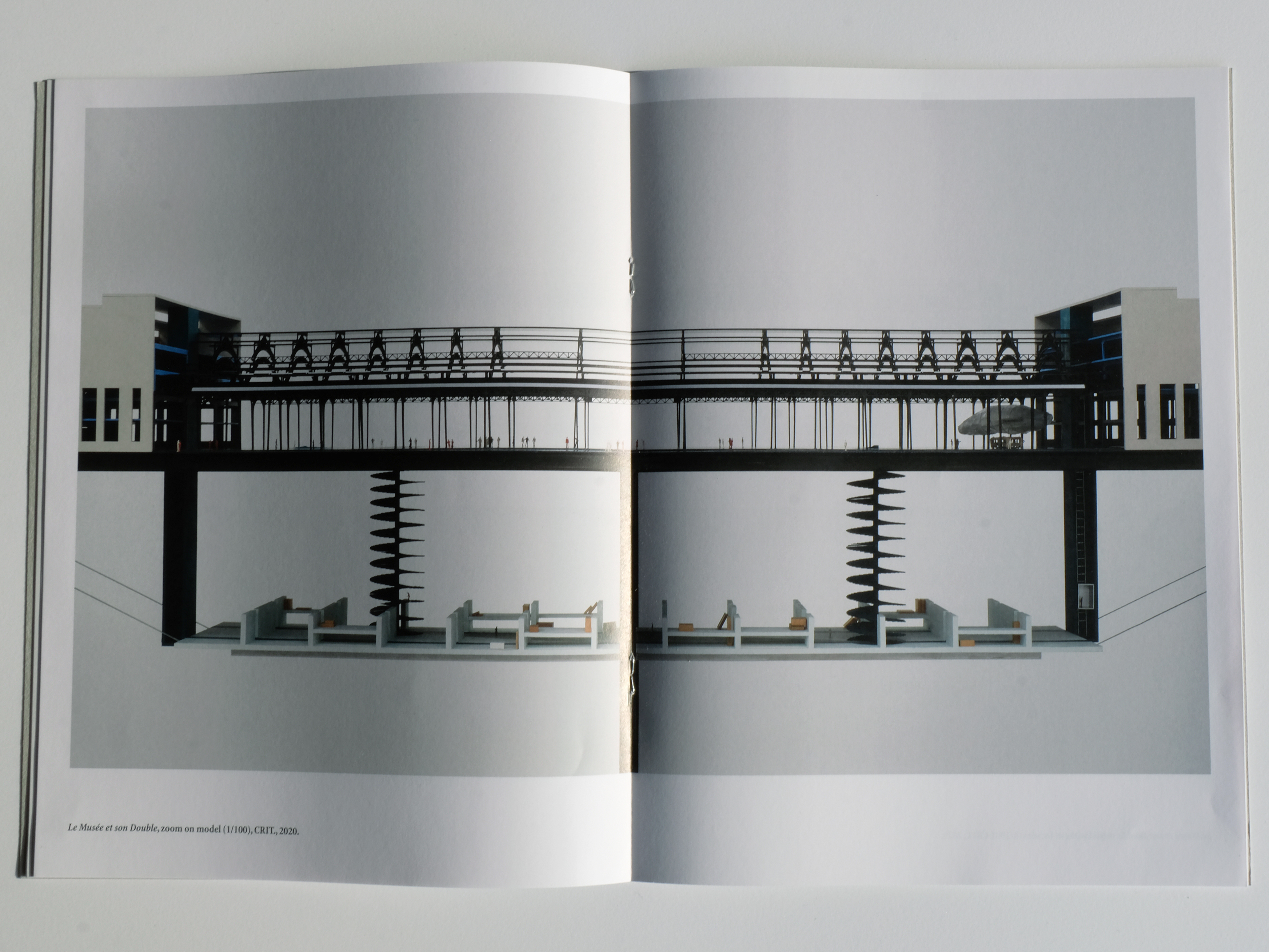

SEVEN (2019/20)

the double museum … This last thought is in effect a challenging one, since it hints irrefutably at S.M.A.K.’s potential architectural future. No longer what has been, but what actually could be. So, let us return to the question of number ‘2’, and take another look at the Floralia complex. The original plans of the greenhouse structures reveal a beautiful symmetrical design, a feature that is presently almost entirely lost. Interestingly enough, the S.M.A.K.’s mirror volume – on the opposite side of the Floralia Hall – has been standing empty forever. What if the necessary ‘doubling in size’ of the S.M.A.K. would result in a double museum? One that would encompass both ends of the Floralia Hall, including an efficient depot underneath the hall? This almost self-evident conceptual scheme would also guarantee that the Floralia Hall would effectively remain public space, instead of a private extension of ’t Kuipke, the Congress Center or any other commercial party. Importantly, in this proposed scheme, the S.M.A.K. would under no circumstances hold any exclusive right to the Floralia Hall. It could make intermittent use of the hall, organize public events, just like any other Ghent stakeholder, cultural organization or social enterprise. Provided the structure were to be given an extensive spatial and technical upgrade, the current S.M.A.K. building could become a place for temporary exhibitions, suitable for both the S.M.A.K. and the Museum of Fine Arts. This would allow the latter to present an even larger section of its permanent collection in the Van Rysselberghe building. At the other far end of the Floralia Hall, housing the permanent collection display of the S.M.A.K., the infamous number ‘500’ comes into play. For these spaces, an equally extensive upgrading is required. The museum’s double typology is ultimately completed by a 8 commons, The Floralia Hall, as a blank hyphen in the park, in the city. To be claimed by no one and enjoyed by everyone. The ultimate public architecture.

P.S.

When it comes to the Citadel Park’s equilibrium, the abovementioned logic can be pushed even further. A view on the park’s satellite image clearly reveals a cluster of commercial programs and large-scale functions that ultimately have nothing to do with a city park. It takes only a vigorous Photoshop exercise to delete all these superfluous structures and reinstate the park’s natural balance. The resulting image is astonishingly beautiful and precise. Simply a line – the Floralia Hall flanked by the double S.M.A.K. museum – and a dot – the Museum of Fine Arts. A new and contemporary museum typology seems to have emerged.

[1] Philippe Van Cauteren, Thibaut Verhoeven and Iris Paschalidis, Highlights for a Future, The Collection, (2019)

[2] Extra muros exhibitions, e.g. Chambres d’Amis (1986), Over the Edges (2000), … Public activism, e.g. ‘Het S.M.A.K. is te klein’ (2019)

[3] Richard Armstrong, Highlights for a Future, The Collection, (2019)

[4] The Ghent Museum of Fine Arts collection comprises more than 9.000 art pieces, ranging from the Middle Ages to the first half of the 20th century. The museum is a knowledge centre for the art of the 19th century, the fin de siècle and the early 20th century. The collection of the Ghent Museum for Contemporary Art (S.M.A.K.) holds more than 3.000 art works, from 1945 onwards.

[5] Koen Brams, Dirk Pültau. Interview with Marc De Cock, former president of the Society for the Ghent Museum of Contemporary Art (part 4), De Witte Raaf, Edition 181 (2016).

[6] The Floralia Hall was built as a temporary flower show structure at the occasion of the 1913 World Exhibition, destined to be shipped to Kinshasa after the exhibition to be given a second life as a railway station. The move never happened.

Editor: Peter Swinnen

Date: 2020

Contributors: Iwona Blazwick, Aslı Çiçek, David Peleman, Peter Swinnen, Philippe Van Cauteren

Design: Inge Ketelers

Publisher: S.M.A.K.

ISBN: 978 90 7567 9595

Edition: 1 000 copies [Dutch], 1 000 copies [English]